Writing in 2012, Janine Natalya Clark, Professor of Gender, Transitional Justice and International Criminal Law at the University of Birmingham, articulated significant criticisms of government policy toward the branitelji, following up on field work she conducted in Vukovar. She pointed out, for example, that the term bivši branitelji (‘former defenders’) is never used, highlighting the persistence of a wartime identity into the present day. The cultural connotations of the word branitelj are as such representative of a consistent trend in Croatia’s post-war policy – meticulous curation of the memory of the Homeland War, and with it, the example of those citizens who fought, as pillars of the state’s identity. They are entitled to significant privileges from the state, including but not limited to generous pensions, preferential employment opportunities and scaled invalidity benefits for those who have suffered lasting disability due to their military service. As of December 2012, the official Register of Croatian Defenders listed 502,768 names and continues to grow.

A respected but isolated community

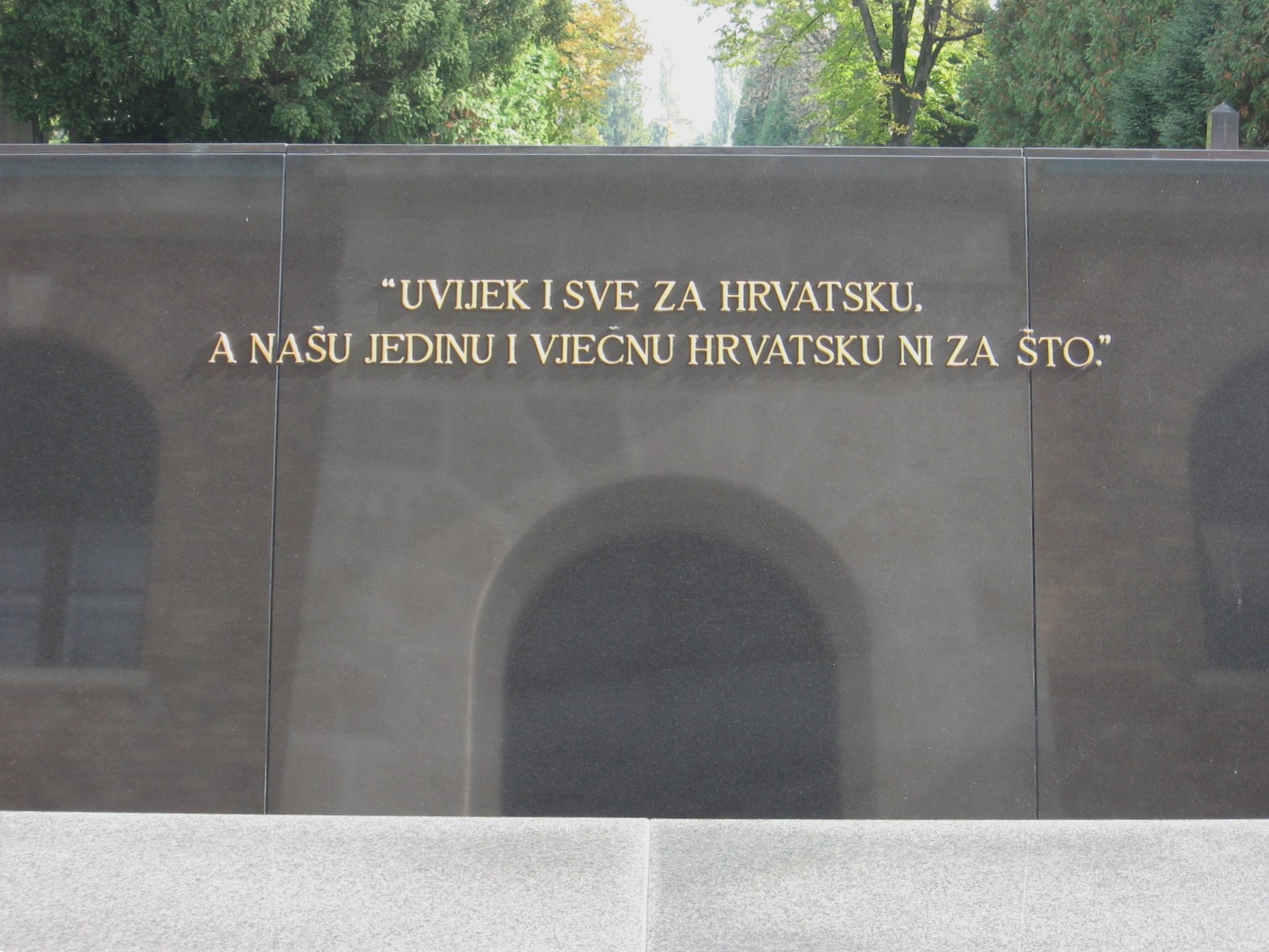

Clark argues that the exclusive nature of the branitelj identity, forged in wartime and relentlessly reinforced in peacetime, hinders these veterans’ reintegration into civilian life. Croatia is consequently deprived of this community as a possible key to peacebuilding between ethnic groups. It has been amply demonstrated in other former conflict zones, for example in Northern Ireland, that former combatants can play a crucial role in building bridges between historically warring communities. However, Croatian state policy, Clark asserts, overwhelmingly contributes to keeping the Croatian branitelji isolated. This isolation also keeps them politically manipulable – in the words of Michaela Schäuble, “due to their indeterminate status between publicly acknowledged heroism and social oblivion”. That acknowledgement is expressed, for example, at official commemorative events, where the branitelji are consistently showered with praise and reverence from dignitaries and other public figures. In particular, the relationship between the branitelji, as a powerful constituency, and Croatia’s governing party, the HDZ (Hrvatska demokratska zajednica, Croatian Democratic Union), is repeatedly reaffirmed through such gestures as then-Prime Minister Jadranka Kosor’s public declaration of thanks to Croatia’s defenders on 5th August 2011, during the commemoration of Operation Storm in Knin, which Clark attended as a participant observer.

Despite being generally viewed with respect, notable barriers exist between the branitelji and the communities which surround them. While financial assistance is commonly rendered by post-conflict governments as an interim measure to aid the “reinsertion” of veterans into civilian society, the benefits which Croatian branitelji enjoy often decreases their motivation to find paying work, and can thus be characterised as a devastatingly short-sighted policy of the HDZ. Clark’s interviews revealed a consequent feeling of resentment towards the ex-combatant community from ordinary civilians, due to their privileged position of being able to survive solely on generous state benefits. This problematic intra-community relationship cuts both ways. One typical element of the entrenched and militarised branitelj identity is the belief that “civilians cannot possibly understand what war was all about. Consequently, there is a discomfort, if not unwillingness, to share deeply about war experiences with non-veterans and the community”. While simultaneously reinforcing the veterans’ sense of self as well as the macro-identity of the group, this repeated affirmation of ‘branitelj’ as the primary identity (and a highly exclusive one) does nothing to promote reintegration, and indeed can be said to actively inhibit it. The multi-sourced nature of the branitelj identity is consistent with Bourdieu’s theories regarding the ineluctable role of society in the formation of self-image and the creation of meaning. Bourdieu posits that “it is… society alone, which dispenses, in varying degrees, the justifications and reasons for existing”. This feeling of “counting for others, in being significant for them”, has also been effectively deployed by Nir Arielli as an explanation for the motivations of foreign volunteers in the Homeland War. It is this significance which, Bourdieu reasons, provides “a kind of continuous justification for existing”.

Identity issues compound effects of trauma

Natalija Bašić has described how many soldiers “had hoped for a post-war position similar to that enjoyed by those who fought in the Second World War – i.e., prestige in society, privileges, careers and positions in the military, society or politics”. When it became clear that they faced a very different reality, one which is “embedded in the contradictory context of rhetorical glorifications on the one side, and low social status as well as suppressed feelings of guilt on the other side”, a wholesale reconstruction of identity was required. This naturally entails significant difficulties. The authority and prominence among their peers which was originally conveyed upon them during the war is difficult to relinquish during the transition to civilian life. As such, a reflexive process of identity construction and reinforcement based on the wartime self becomes necessary, to avoid the feared outcome of becoming ‘nobodies’: a process which can be psychologically damaging.

The mental health status of Croatian branitelji constitutes a related and aggravating factor. According to a 2007 report by the European Network of Economic Policy Research Institutes (ENEPRI), “a considerable share of the veterans’ population suffers from various war traumas which affect their social functioning, particularly post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Furthermore, [this is] without a doubt the group with the highest suicide rate.” And suicide is only the most extreme consequence of trauma suffered by veterans. Many others seriously imperil their prospects for successful reinsertion into civilian life – an inability to form trusting relationships, a higher tendency towards aggression including domestic violence, alcoholism, and drug abuse are all frequently observed – and are suffered also secondarily by loved ones. It is indisputable that one of society’s key obligations towards the branitelji is to provide not only economic aid, but also socio-psychological assistance to those who need it.

The challenges to this are, however, immense. Clark primarily highlights the unwillingness of many veterans to take advantage of such services due to cultural stigma surrounding psychological illness. This is exacerbated by traditional attitudes toward masculinity, widespread in Southeast Europe, which work to strongly discourage admissions of vulnerability. Indeed, such an admission can be perceived as anathema to the core values for which they are constantly showered with praise – heroism, bravery and courage – and even acknowledging their trauma, let alone reaching out for support in managing it, would be incompatible with their militarised identity. Clark suggests that a positive publicity campaign involving “prominent and well-respected veterans” could go a long way towards reducing this stigma and replacing it with recognition that a request for assistance is also an expression of strength and courage. Such socio-psychological support among veterans could be aided, furthermore, by a change in terminology surrounding PTSD. The US military took decisive steps in this direction with the coinage of ‘combat stress reaction’ (CSR), a denomination which removes the “disorder label” and with it aims to mitigate the averse social reaction to what is, at various levels of severity, a common reaction among military personnel. Indeed, as Raymond Scurfield describes, the introduction of the term CSR goes a long way toward recognising that responses to wartime stressors may not be disordered, but rather completely normal in the highly exceptional environment of war. What is far from normal, however, is the state’s failure to comprehensively address a deep-rooted social issue which will continue to undermine the complete recovery of Croatia from its conflict-ridden past.

Bašić, N., ‘Kampfsoldaten im ehemaligen Jugoslawien: Legitimationen des Kämpfens und Tötens’. In: Seifert, R. (ed.) (2004), Gender, Identität und Kriegerischer Konflikt. Das Beispiel des ehemaligen Jugoslawien, 89-111 (Münster: LIT)

Clark, J. N., ‘Giving Peace a Chance: Croatia’s “Branitelji” and the Imperative of Reintegration’, Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 65, No. 10 (December 2013), 1931-1953

Schäuble, M., ‘Imagined Suicide: Self-Sacrifice and the Making of Heroes in Post-War Croatia’, Anthropology Matters, Vol. 8, No. 1 (2006)